We must act now to safeguard future space use

The space industry has been expanding at a remarkable rate in recent years, with a steady increase in both commercial and non-commercial activity. Most notable is the growth seen in the low Earth orbit (LEO) satellite market which is projected to grow from USD 9.6 billion in 2021 to USD 19.8 billion by 2026. In two years, the number of active and defunct satellites in LEO has increased by over 50%, to about 5,000 (as of 30 March 2021).

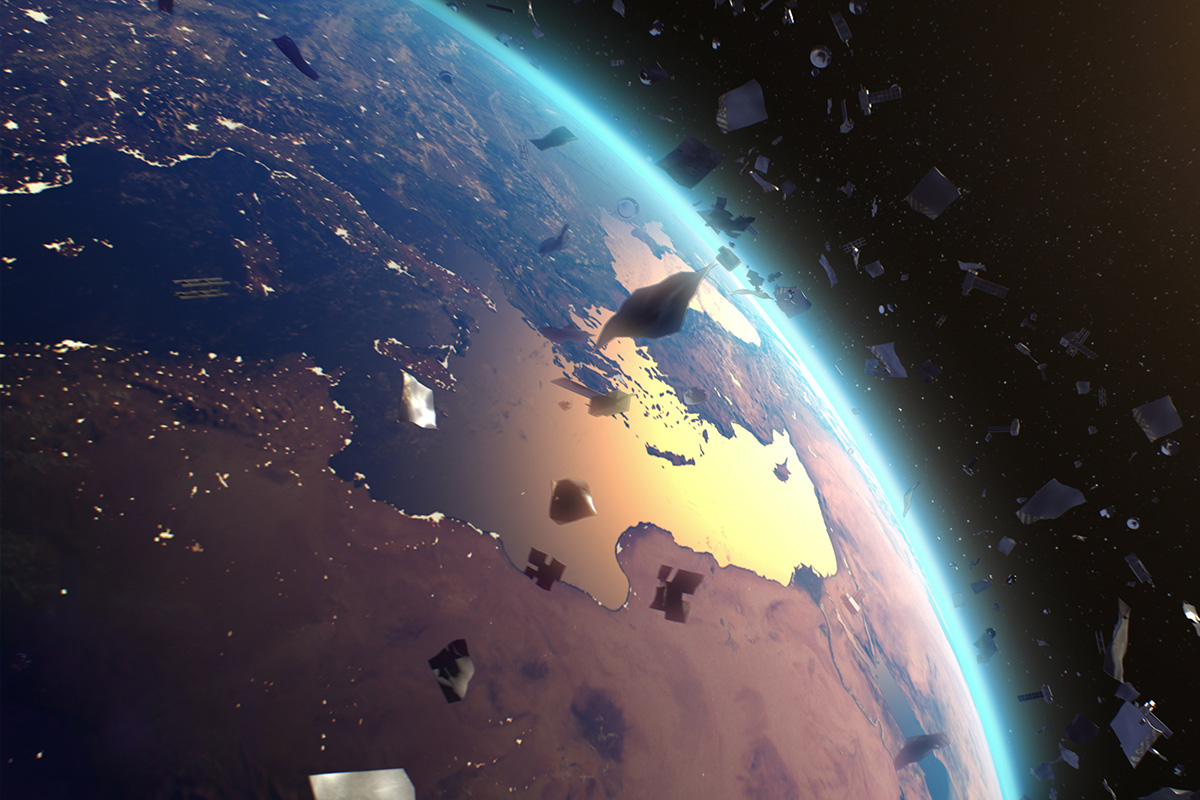

More traffic = more debris

Unfortunately, increased activity leads to increased quantities of orbital debris. According to NASA, more than 27,000 pieces of debris are tracked by the Department of Defence’s global Space Surveillance Network (SSN) sensors.

NASA has also reported that two single events are responsible for increasing the amount of space debris by a whopping 70%, namely the destruction of the Chinese Fengyun-1C spacecraft in 2007, and the accidental collision of an American and a Russian spacecraft in 2009.

However, the larger pieces of debris, capable of being tracked are arguably less of a problem than smaller pieces that can evade surveillance systems. Even small pieces of debris, not much bigger than a football, are capable of causing considerable damage to satellites and spacecraft. This is no surprise when you consider the speeds involved. Debris and satellites in LEO are travelling at around 15,500 mph and so a collision at such high speeds would obviously cause significant damage.

Removing debris is another important aspect of its management. It is good to see new approaches to debris removal being developed, such as the ESA commissioned ‘claw’, but above all, any further activity needs to stop contributing to the problem.

Shared responsibility

All space users have a shared responsibility to ensure that the entire satellite life cycle is carefully managed to avoid debris, right from the initial launch, through its operation to the end of life when it is decommissioned. Governments need to play a role in regulating this area but getting the balance right is vital. A heavy-handed approach to regulation is likely to result in some countries withdrawing from engagement. A lighter regulatory touch, on the other hand, is much more likely to bring about the desired outcomes.

Yes, tracking, removing, and preventing new debris is a key area but it is not the only concern. With many more satellites due to launch, particularly into LEO, many are concerned about the risk this poses to the entire space environment. Space Traffic Management (STM) is a core part of managing space sustainably. For better in-orbit safety, there is a need to improve tracking of small objects, improve orbit determination activity, have better data sharing and create requirements for all active satellites to have the capability to perform collision avoidance and de-orbiting/re-orbiting manoeuvres.

What are the hurdles to better in-orbit safety?

Without accurate and coordinated STM Services, increased activity in space obviously magnifies the risk of collision, accidents, misunderstandings, and conflicts. While complex, existing STM systems are technically capable of providing in-orbit safety so if technology is not the barrier to better in-orbit safety, then what is? As is so often the case with global ventures of this magnitude, cost, data sharing, and politics are all holding back progress in developing any kind of centralised system. The sheer scale of space makes cost a real issue when it comes to developing better STM systems. It is critical that government funding plays a significant role within STM management.

For a centralised system to be reliable, accurate and effective, data would obviously need to be fed into the system from Ground/Space sensors but also by all space users and this would need commitment and industry wide cohesion. This is not a straightforward ask because not only is the positions of craft and objects sometimes uncertain, data may also be kept private for commercial, political and governmental security reasons.

What next?

Underlying the challenges outlined above is a lack of worldwide and industry-wide cohesion. Private organisations have capabilities to provide monitoring and data processing to mitigate in-orbit collisions, so it is vital that the private and public sectors work together to pool resources and investment. A cohesive global approach to STM funding would allow creation and management of high level, fit for purpose STM systems.

One potential way forward through the political and data sharing maze is for the development and maintenance of a publicly funded Global Space Objects catalogue based on data fusion, that is employed alongside a central private system processing the catalogue data.

One thing that is very clear is, the time to act is now. Unless steps are taken to develop a central STM system, improve tracking of small objects, prevent new space debris, improve orbit determination activity, launch satellites capable to perform collision avoidance with debris and have better data sharing agreements, the risks of accident and collision will simply increase. This increased risk has the potential to impact not just space users, but also those businesses and individuals around the globe who rely on satellite connectivity (even if they don’t realise it) for so many daily activities.

The future sustainability of space is in doubt and if a global agreement ensuring that all space users adhere to best practices is not signed now, tomorrow’s space use may well be limited.